Progress Made To-Date

Updated April 2020

TBA

Original Action Step 4 Directive from 2017:

Real progress happens at the local level. Few care and know more about a neighborhood than its own residents. During the planning process, the lack of neighborhood level engagement emerged as one of the most significant missing links or hurdles to real canopy progress in Charlotte. For this reason, a critical next step is to create a framework to involve and engage neighborhoods at the local level. Citizens must affect change and improvement. Assistance and guidance should be provided by the city, TreesCharlotte, and other relevant stakeholders.

Local engagement is also important because one size does not necessarily fit all. Each community within Charlotte will have different urban forestry goals, values, needs, and priorities. This diversity is what makes cities unique. One way to involve local communities is to work with them to develop "mini master plans." This work will explain the citywide master plan and foster establishment of local goals and priorities that fit into the master plan framework. It is important to convey to citizens that they are part of a bigger movement but are taking action locally.

Better local boundary establishment and resident association will serve a number of purposes, beyond supporting the creation of local teams of canopy supporters and volunteers. It will also support city departments in better communication with local neighborhoods (also a recommendation of this plan), and can provide local residents with an avenue of inquiry to the city as well.

Next Steps: A number of steps will be needed as part of this effort:

Local engagement is also important because one size does not necessarily fit all. Each community within Charlotte will have different urban forestry goals, values, needs, and priorities. This diversity is what makes cities unique. One way to involve local communities is to work with them to develop "mini master plans." This work will explain the citywide master plan and foster establishment of local goals and priorities that fit into the master plan framework. It is important to convey to citizens that they are part of a bigger movement but are taking action locally.

Better local boundary establishment and resident association will serve a number of purposes, beyond supporting the creation of local teams of canopy supporters and volunteers. It will also support city departments in better communication with local neighborhoods (also a recommendation of this plan), and can provide local residents with an avenue of inquiry to the city as well.

Next Steps: A number of steps will be needed as part of this effort:

1. Define Neighborhoods/Working Areas. During the planning process, many residents cited the desire to get involved but didn't know how they could do so locally. When residents were asked what neighborhood they lived in, most could not easily identify the neighborhood, citing instead either the side of the city they lived in (i.e. southeast Charlotte), or the names of their particular developments or subdivisions. This is the most significant hurdle to local engagement - the lack of 1) established neighborhood boundaries, and 2) resident identification and association to that neighborhood (by name).

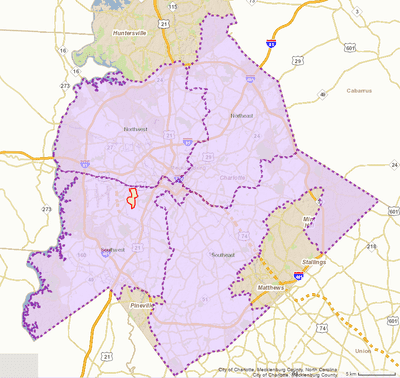

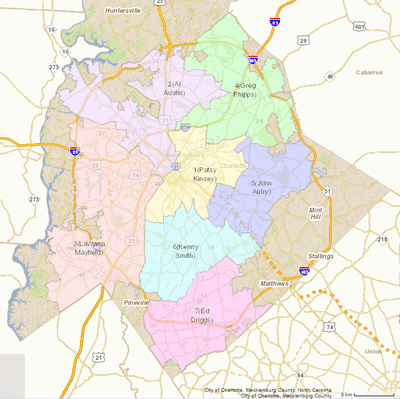

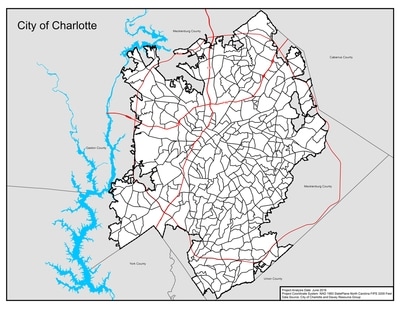

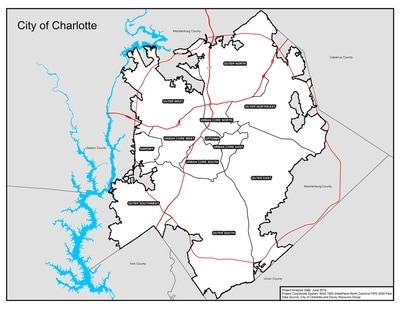

The city currently operates with a number of boundary frameworks. Neighborhood & Business Services uses four service areas—southwest, northwest, northeast, and southeast—to organize their efforts. Charlotte is also divided into 7 council districts. The Planning division organizes neighborhoods into over 300 different places, though neighborhoods are not named (each is assigned a number), nor do they represent any organization recognized by residents (aside from a few well established neighborhoods).

Here are a few examples of the local boundaries currently in use today:

The city currently operates with a number of boundary frameworks. Neighborhood & Business Services uses four service areas—southwest, northwest, northeast, and southeast—to organize their efforts. Charlotte is also divided into 7 council districts. The Planning division organizes neighborhoods into over 300 different places, though neighborhoods are not named (each is assigned a number), nor do they represent any organization recognized by residents (aside from a few well established neighborhoods).

Here are a few examples of the local boundaries currently in use today:

Image Sources: NBS Service Areas / Council Districts map from http://vc.charmeck.org/

However, if forming well-defined, official, named neighborhoods is not feasible, other alternatives could be considered. Residents can be given the option to create their own neighborhood boundaries, or conversely, the city arborist can define named working areas (explained in more detail in the management plan recommendation), and residents can then be informed of said working areas. No matter the avenue taken, it is important that working boundaries are established and coordinated with existing systems as much as possible to avoid confusing overlapping boundaries. Once defined, an online tool could be created to help residents figure out which neighborhood they live in and how to get involved.

However, if forming well-defined, official, named neighborhoods is not feasible, other alternatives could be considered. Residents can be given the option to create their own neighborhood boundaries, or conversely, the city arborist can define named working areas (explained in more detail in the management plan recommendation), and residents can then be informed of said working areas. No matter the avenue taken, it is important that working boundaries are established and coordinated with existing systems as much as possible to avoid confusing overlapping boundaries. Once defined, an online tool could be created to help residents figure out which neighborhood they live in and how to get involved.

2. Identify Local Champions. Once working areas are defined, neighborhood champions or ambassadors should be identified and utilized as a conduit for communication and updates between the city, TreesCharlotte, and residents on all tree canopy efforts (read more about how Pittsburgh engages local leaders in the case study below). These local champions could serve as an informal group or also serve on the city's Tree Commission to provide full and equal representation to each area of the city.

3. Provide Access to Data. Inspire, enable, and empower neighborhoods to make their own changes by providing them with the data they need to affect change. In today's high technology world, people expect to be able to access data and maps directly. This can include tree canopy cover, land use data, future planting sites, benefits from the existing trees, and more.

4. Set Local Goals and Next Steps. Once neighborhoods and champions are identified and data is made available, the next logical step is to work on setting goals and a plan of action for each area. This can be done multiple ways, though the most effective way may be hosting a one-day planning session to identify current conditions, challenges, needs, goals, and next steps. Work can be planned within the framework of the larger master plan, pairing the unified voice with local action. This meeting also provides another opportunity for the city to better communicate their processes and priorities to local residents (also a recommendation). Groups could be provided with a starting menu of projects or programs to implement (i.e., cankerworm banding program, community inventory, tree plantings, adopt a tree or tree stewardship training). Potential starter funds could also be provided to groups that complete this training and planning process. The City of Cincinnati has a similar program to assist neighborhoods to set and achieve their own goals, as explained in the case study below.

5. Implement. Depending on the projects or efforts chosen, neighborhoods can implement their efforts in coordination with the city and TreeCharlotte's management plan. Read more about how all of these efforts can be coordinated and implemented in concert - the city's efforts, combined with TreesCharlotte and Charlotte's neighborhoods.

6. Regular Check-In. Schedule annual check-ins with each neighborhood group (via meeting, annual event) to evaluate progress to date and to make any adjustments. This provides an opportunity to update neighbors on what the community has done, what the challenges are, and what the city is working towards.

Potential Owners: TreesCharlotte, City of Charlotte (NBS, Erin)

Potential Participants: Universities (students could provide neighborhoods with UTC data reports), neighborhood groups/entities like Center City, etc. Tree Commission

3. Provide Access to Data. Inspire, enable, and empower neighborhoods to make their own changes by providing them with the data they need to affect change. In today's high technology world, people expect to be able to access data and maps directly. This can include tree canopy cover, land use data, future planting sites, benefits from the existing trees, and more.

4. Set Local Goals and Next Steps. Once neighborhoods and champions are identified and data is made available, the next logical step is to work on setting goals and a plan of action for each area. This can be done multiple ways, though the most effective way may be hosting a one-day planning session to identify current conditions, challenges, needs, goals, and next steps. Work can be planned within the framework of the larger master plan, pairing the unified voice with local action. This meeting also provides another opportunity for the city to better communicate their processes and priorities to local residents (also a recommendation). Groups could be provided with a starting menu of projects or programs to implement (i.e., cankerworm banding program, community inventory, tree plantings, adopt a tree or tree stewardship training). Potential starter funds could also be provided to groups that complete this training and planning process. The City of Cincinnati has a similar program to assist neighborhoods to set and achieve their own goals, as explained in the case study below.

5. Implement. Depending on the projects or efforts chosen, neighborhoods can implement their efforts in coordination with the city and TreeCharlotte's management plan. Read more about how all of these efforts can be coordinated and implemented in concert - the city's efforts, combined with TreesCharlotte and Charlotte's neighborhoods.

6. Regular Check-In. Schedule annual check-ins with each neighborhood group (via meeting, annual event) to evaluate progress to date and to make any adjustments. This provides an opportunity to update neighbors on what the community has done, what the challenges are, and what the city is working towards.

Potential Owners: TreesCharlotte, City of Charlotte (NBS, Erin)

Potential Participants: Universities (students could provide neighborhoods with UTC data reports), neighborhood groups/entities like Center City, etc. Tree Commission

|

Case Study: Pittsburgh's Small Neighborhood Urban Forestry Plans. After completion of a citywide urban forestry master plan in 2012, Pittsburgh began helping local neighborhoods create their own customized version of the master plan at the neighborhood level. By teaming up with local development corporations, a neighborhood ambassador, representatives from city planning and city forestry, the local Tree Tenders group, the area's business association, and interested local residents, TreePittsburgh has worked with the group to review existing conditions (canopy cover, tree count and condition, and potential planting sites) with local goals, needs, and costs in mind. They help the neighborhood create and implement their own program vision and goals in line with the citywide master plan. Learn more about Pittsburgh's budding local neighborhood planning.

|

Case Study: Combining Urban Forestry Efforts with an Overall Neighborhood-Wide Improvement Program (Cincinnati)

Cincinnati’s award-winning Neighborhood Enhancement Program (NEP) is an incentive program offered by the city to create local action and progress with minimal costs. NEP is a 90-day collaborative effort between city departments, neighborhood residents, and community organizations. Each year, one neighborhood is chosen to participate in an intensive enhancement program. The neighborhood is provided with funding (typically supplemented by local fundraising) and receives planning assistance and direct access to all city departments. The work spans many different goals and needs of the community but often includes tree planting, tree care, and other tree canopy projects. Other work has included cleaning up streets, sidewalks, and vacant lots; general landscaping; streetscape and public right-of-way improvement; addressing crime and code violations; and engaging property owners and residents to create and sustain a more livable neighborhood. Learn more about Cincinnati's NEP.

Cincinnati’s award-winning Neighborhood Enhancement Program (NEP) is an incentive program offered by the city to create local action and progress with minimal costs. NEP is a 90-day collaborative effort between city departments, neighborhood residents, and community organizations. Each year, one neighborhood is chosen to participate in an intensive enhancement program. The neighborhood is provided with funding (typically supplemented by local fundraising) and receives planning assistance and direct access to all city departments. The work spans many different goals and needs of the community but often includes tree planting, tree care, and other tree canopy projects. Other work has included cleaning up streets, sidewalks, and vacant lots; general landscaping; streetscape and public right-of-way improvement; addressing crime and code violations; and engaging property owners and residents to create and sustain a more livable neighborhood. Learn more about Cincinnati's NEP.